One interesting and yet mundane aspect of life on Home Island is the living arrangements. Throughout living memory Cocos Malays have lived in and modified homes built to exactly the same plan.

|

Houses built 1985-1992

(Nicholas Herriman)

|

Since settling on this remote atoll, the majority of Cocos Malays have lived on Home Island. Although at various times, some have lived on other islands in the atoll. For instance in 1941, of the 1450 residents of Cocos Islands, some lived on Horsburgh Island (Gibson Hill 178). My concern in this blog use with the living arrangements on Home Island. What were they like in the past and how have they changed? What I would really like to know however is whether the past provides insight into the way Cocos Malays currently use their homes.

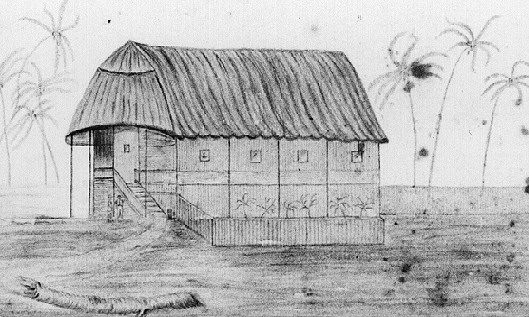

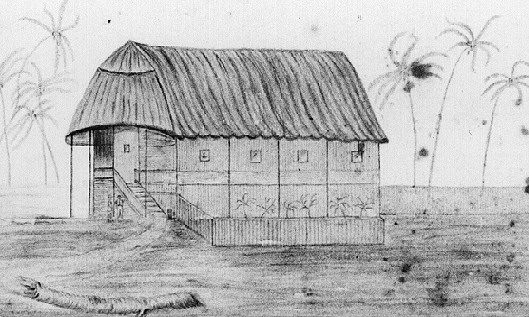

Darwin's 1836 visit

In April 1836, Charles Darwin and the crew of the HMS Beagle visited the Cocos Islands. Darwin's assistant, Syms Covington, made the following sketch of what appears to be a two-story, thatched-roof structure.

|

| http://www.asap.unimelb.edu.au/bsparcs/covingto/gifs/keeling.jpg |

Unfortunately, I can't find any commentary in Covington's journal on this structure. It may not, for example, have functioned as a home. But the illustration does match well with Darwin's April 3 diary entry notes,

"Capt Ross & Mr Liesk live in a large barn-like house open at both ends & lined with mats made of the woven bark: the houses of the Malays are arranged along the shore of the lagoon".

Syms Covington's sketch seems to match the "large barn-like house".

This is corroborated by the captain of HMS Beagle who notes that Ross and Liesk:

had wives (English) and children, the whole party residing together in a large house of Malay build—just such a structure as one sees represented upon old japanned work.

Belcher's 1846 visit

An English explorer, Edward Belcher, visited in 1846, and wrote:

“I certainly expected to find the residence of Capt Ross after the lapse of twenty years – in a decent condition. It presented however – nothing more than such a House as could be rapidly raised from the timbers saved from a wrecked vessel – and gloomy beyond conception – being completely overshadowed by coconut trees and as a natural consequence swarming with mosquitos. The Malay village was infinitely more inviting (Belcher, Narrative

of the Voyage, 1848, p. 194)."

This angered Clunies-Ross. Clunies-Ross reacted by saying that Belcher's expectations were too high ("Preface" pp. 159-160).

Late 1800s: Two residential areas

In the late 19th century, there were two residential areas or kampong. In one the descendants of the original settlers resided. They were called "Orang Cape" (Cape People), as the original settlers had lived in the Cape of Good Hope before moving to the Cocos Islands. In the other kampong resided Orang Banten (Bantamese). These were convicts who had been sent out from from West Java, to serve part of their terms as indentured laborers on the Cocos Islands.

Houses have changed

markedly in the living memory of Cocos Malays. This change came in three stages, discussed in the following three sections respectively. A cyclone (hurricane) had destroyed most of the Home Island residences in 1909.

1920s-1950s Rumah Atap

With great effort, it appears, new homes for all the residents were built in the 1920s and used into the 1950s. We could call these the 'Thatch Roof' (Rumah Atap) homes.

These “243 houses", Gibson Hill (176) writes, were "all identical in size and outward appearance, arranged regularly in straight, parallel rows”:

They were plain, rectangular buildings, about eighteen feet wide and twenty-six feet long. In most cases the interior was divided by partitions to form two small rooms, which were used for sleeping, and a large room which was used for the reception of visitors. There was a door in the centre of each end, and usually one half way along one of the sides.

|

A diagramatic representation of a house in the kampong on Home Island, with part of the wall and roof removed to show the internal structure. The supporting beams have been labelled with their local Malay names. (Gibson Hill 178)

|

|

| Layout of the Home Island village in 1941 (Gibson Hill 176). Note the neat rows of houses. |

Pauline Bunce (92) note that these new houses:

constructed with local building materials. They were built off the ground on top of short stumps. The walls are made from a kind of cane, obtained from the spine of the palm frond, the frame was made from local hardwood and the roof from layers of woven palm fronds (Bunce 92).

So what was life like in these homes? I showed Nek Su (Remni Mochta, June 6, 1942). the following photo and this is what he recalled:

This is what we call Kampong Atas; it's close to the beach. It wasn't all that comfortable. We used oil lamps so we couldn't really see [inside the house]. Many rats lived in the coconut leaves. The rats and people lived together. There were six in my family while I was young. I often stayed with my grand[mother], [Nek] Daniel

|

(Gibson Hill, Plate 3) Nek Su recalled: This is the kampong that is close to the mosque--Kampong Tengah. These houses had one dining room with two bedrooms (like the subsequent "Stone Houses"). They were made from coconut tree and had walls of "plepa". In those days there wasn't any asbestos. As time went on some people took the thatch off and replaced it with corrugated iron.

John Hunt (1989, 26) describes the rumah atap as follows: The houses were 20 feet (6.15m.) wide and 26 feet (8m.)

long, standing in gardens about 115 feet (35m.) long and 30 feet (9.20m.) wide,

bounded by wooden fence. A kitchen/store-room and a bath house stood behind each- home.

All buildings were made from local materials. The roofs were made of

thick "atap" (coconut thatch). Every house was numbered, with the

owner's name written above the front door. The sign was sometimes decorated to

the owner's taste with a picture of a bird, a star or a crescent moon.

|

1950s-1980s Rumah Batu (Stone Houses)

1950s-1980s people lived in "Stone Houses" (Rumah Batu). These were also laid out in rows according to a single model plan. The material differed, the walls being made form rocks quarried from the beach. They were built in the 1950s in the the context of a post-war huge emigration (the majority of Home Islanders had emigrated to Malaysia after the war) and the rule of new King, John Cecil Clunies-Ross. The houses':

walls were cast in such huge moulds and the design was similar to the earlier atap model. Wooden kitchens, storage sheds and wash houses were built separately at the back, as before. Water for household use was drawn by hand from backyard wells right up until the 1980s (Bunce 92)

|

|

The 1950s style of house.

http://photos.naa.gov.au/photo/Default.aspx?id=11487349

|

Nek Su recalled:

We called these "Rumah Batu" (Stone Houses). The kitchen was on the outside there wasn't a kitchen inside. There were two bedrooms and a lounge room. There must have been built in the 1960s. My father, Mochta Salip, built these because he was the chief carpenter. We got the concrete from the back of the island. The parts were numbered 1, 2, 3 and then put together. The rocks were from here.

The plans for the next style of home, the New Houses, depict and "Existing Ablution Block". It thus appears that the ablution blocks which are still used today were built at some point while the Stone Houses were used.

Rumah Baru (New Houses) 1980s-now

From 1980s till now, Home Islanders have resided in the 96 "New Houses" (Rumah Baru). As part of the Home Island Development Plan, these were built to the same plan. One aspect that was flexible was the number of bedrooms out the back— houses with more bedrooms were built for larger families.

|

| New House (left) and Stone House (right) (Bunce 92) |

I contacted the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development about the Home Island Development Plan. Steve Clay and his associates were incredibly helpful, sending information in an email that I have paraphrased and added to in the following paragraphs.

The decision to build new houses was reached in 1983. The program was called "the Home Island Development Plan", or "HIDP" for short. According to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Annual Report 1983-84 "in December 1983 the Government announced its commitment to a development plan for Home Island...the community has chosen the house design to be constructed under the Development Plan... Construction by the Cocos Co-Operative and Department of Housing and Construction will commence early in the 1984-85 financial year.

The design appears to have been democratic. Writing in the 1980s, Bunce (92) notes "The current housing design was developed from the results of extensive surveys of family living patterns and expressions of community desires".

The first houses were finished in 1985. The 1986-87 Annual Report states that "the first home completed under the plan was opened...on 1 May 1985" . The email continues that "the first home completed under the plan was opened...As of the 30 June 1985, four houses had been completed and four more were under construction."

One recurring theme is the use of outdoor kitchen. It appears in all the home designs, Cocos Malays cooked out the back. Even though the latest plan was equipped with a kitchen inside, people have preferred to cook outside.

Now, I think, the kampong is, informally divided into 3 Kampong Baru (on the West by the lagoon); Kampong Tengah (in the middle and incorporating the mosque); and Kampong Kangkung (on the East).

Summary

At each of these three stages, the old houses were entirely replaced. Instead of every house being built to an individual’s own design, all houses were built to the same design, around the same time. Thanks to the hard work of Cocos Malay builders, in effect three entirely new villages have been built, each replacing the earlier one!

Thank you to our new hosts Ayesha and Nek Su for their hospitality and their help with this blog!